Filed under: Peace Corps Romania | Tags: Amers, connection, friendship, human web, MB, Peace Corps, Robert Frost, Romania, sarmale, The Road Less Traveled

There are times when our beautiful web of human interaction makes the world seem so tiny and sacred; yesterday was one of those days.

I woke up to receive an email from Amers, one of my dearest, who is in her first year of Teach for America, in Hawaii. Amers had forwarded me “The Road Less Traveled,” by Frost, along with some hope that my day was good. I re-read the lines, which I had not tasted in at least a year or so, and they were more beautiful and soul-piercing than ever before.

I found “Oh, I marked the first for another day!/ Yet knowing how way leads on to way/ I doubted if I should ever come back” to be more full of simple truth than my young (comparatively) self could have ever known.

I taught and danced through the minutiae that has become my developed, daily routine, and in the late evening I went to Karate class. After I had showered and dressed, I made plans with two of the guys to grab a beer at the bar directly underneath the gym. Just before we entered, I got a phone call from another dearest, MB, who was having a quiet sick-day at his station, in Antarctica.

I stood outside and talked to MB for 15 minutes, and felt like he wasn’t so far away as we giggled, cooed, and smiled in our voices. Then I went inside the bar, and over a 0.5 liter beer, my two friends and I discussed the regional differences of Romanian sarmale.

And life felt so close and simple and snug.

And I realized that, although I am learning to miss the amazing, our human web provides means of maintaining the most basic foundations of connection and friendship.

And although I know how way leads onto way, and I do doubt if I should ever come back to re-live these memories, the world has assured me that distance is indeed difficult, but not at all insurmountable.

And just because we each much take the road less traveled by, does not mean that our paths do not run parallel, and even occasionally come close to intersect again.

Filed under: Peace Corps Romania | Tags: best place in Bucharest, Bucharest, Bucuresti, Guinness, hookah, Lipscani, Peace Corps, quinoa, Romania, sushi, tea shop

My last few travels through Bucharest (Bucuresti), Romania’s capital, have brought me to what I consider the best place in the city: Lipscani.

Lipscani was the commercial center of Bucuresti during the middle ages, and its glory days continued onwards into the 20th century. All of Bucuresti was heavily bombed by the allies during World War II, however, which affected Lipscani’s presence as a commercial district. In 1977, a massive earthquake rocked the south-eastern part of Romania, during which much of Lipscani fell into disrepair. The entire area was tagged by Ceaușescu (Romania’s communist dictator until 1989) to be destroyed and rebuilt into the cookie-cutter ‘blocs’ that cover so many other places in Romania.

Fortunately for Romania, this never happened, and the area stayed ‘asleep,’ and untouched for a few decades.

Now, Lipscani is waking up, and is seeing massive restoration efforts. The result is some of the oldest and most authentic architecture in the entire city. Spires, twists, stones and domes everywhere.

And Lipscani is, to this American-born boy, the most progressive part of the city.

In Lipscani, you can find expensive sushi restaurants, and underground German eateries.

In Lipscani, there are skate shops, tea huts, and importers of all sorts of beautiful paisley and tye-dyed things from Nepal and India.

In Lipscani, you can find dried quinoa, hookah bars, and Guinness on tap.

In Lipscani, you can bump into stumbling Scottish soccer hooligans rolling and cursing from one UK pub to the next.

In Lipscani, you can find alternative life-style clubs carefully tucked under black awnings next to massive wall-sized murals of street-art.

So, in Lipscani, you find the city-feel that pervades places like London, Vienna, and Berlin.

So, Lipscani is the place in Bucuresti that feels like other cities in the EU, sometimes for better, and sometimes for worse.

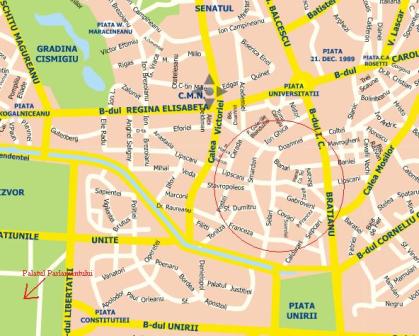

From Piața Universitații, head south, towards Piața Unirii. Walk on the right side of the street. Across the street from the massive, glass-covered mall with large TV ‘steps’ there should be a quiet, cobble-stone pedestrian street. Look for the massive cowboy sign (which may be removed soon) or a staircase disappearing down to traverse across the main boulevard. That’s where you want to be.

Lipscani is inside the red circle

Follow that little, cobbled street into Lipscani’s belly, and disappear for a long while.

Filed under: Peace Corps Romania | Tags: cleansing, Domn Cordea, fast, formal tense, informal tense, judo, karate, martial arts, Peace Corps, Romania, Romanian

This semester I’ve started devoting about six hours per week to martial arts. My school’s sport teacher, Domn Cordea, is a black-belt in two disciplines: Judo and Karate. He holds classes for two hours, four times a week. I usually make three out of the four (the other overlaps my late-Friday teaching schedule).

Domn Cordea is intimidating. He has penetrating eyes, and when he speaks he is deliberate and precise with his words. He tips his hat to any woman that he greets, and he often says things like “my esteemed colleagues,” when he addresses a room full of people. I only have one picture of him; it’s from a teacher’s party my school threw last year.

guess which is Domn Cordea

My own ability to speak Romanian diminishes in his presence, but this is not because I’m afraid of making grammatical errors when I speak to him. Rather, I’m afraid of accidentally addressing him in the “second person informal” tense. Romanian has a formal and informal second person tense, and it can be insulting to use the casual second person when speaking to someone in a position of heightened status.

And I have never heard ANYONE use anything other than the formal tense with Domn Cordea. He is almost sixty years old, so his age demands respect. He was also my school’s director for a long period of time. These things, including his mere presence, demand the formal tense. My school directors, visiting police officers, and members of the local government all speak to him the formal tense. In fact, I don’t even know what his first name is. To everyone he is simply “Domn Profesor,” or “Domn Cordea,” and with everyone he always uses the casual, informal tense.

He has told me stories of the training he did when he was younger: doing fist push ups on sheets of ice outside when it was -20 degree Celsius (-4 Fahrenheit). He has told me stories of how easy army training was in comparison to the enormous rigors of martial arts conditioning that he has subjected himself to.

It seems that his mental toughness has only strengthened with age. When I arrived in site, last year, Domn Cordea was very skinny. He only weighed about 60 kilograms (132 lbs). He told me something about “treatment,” but in my low-Romanian ability, I could only piece together the conversation by guessing. I estimated that Domn Cordea was very sick, and was undergoing a harsh treatment to heal himself. Soon thereafter, he stopped treatment, and started gaining size again.

One recent evening, after two hours of karate, Domn Cordea told me he was undergoing treatment again. This time, I was able to understand that the ‘treatment,’ was a self-imposed, cleansing ritual that he does once a year. It consists of this: Domn Cordea will eat nothing for the next 40 days. He will drink only herbal tea until the treatment is over. This is what I’ve understood.

“By the time I’m done, I’ll be only bone,” he laughed and showed me his bicep, which was already shrunken and lean after 14 days straight of fasting.

I laughed in solidarity, and fascination, and I could not say anything except “yes, yes.”

Filed under: Peace Corps Romania | Tags: body art, Directoara, Luna, Miner, Peace Corps, piercings, Placement Officer, professionalism, Romania, tatoos

My post “Tattoos” is my most popular Peace Corps blog post, according to my stats page. I’ve realized that most of its hits come from search traffic that include the phrases “Peace Corps,” and “tattoos.” Hence, it seems pretty clear that potential volunteers are sifting through blog pages trying to find some enlightening words regarding Peace Corps’ official stance on body art, and how that pertains to a volunteer’s service.

So, here’s my experience with tattoos and piercings, in the Peace Corps:

When my Peace Corps Placement Officer called me late in March of 2008, to discuss my placement in Eastern Europe, at one point he asked about my tattoos. I have couple-inch-wide bands wrapped around both forearms, just below my elbows. They are completely visible when I wear short-sleeved shirts:

'PROMETHEUS' and 'EUDEMONIA'

My Placement Officer said the tattoos could be a problem, as tattoos are not prevalent in other parts of the world, and carry a negative stereotype. He told me it would be best if I covered them at all times, and kept them hidden from public view. This spooked me, and I went out and bought multiple sets of UnderArmour forearms sleeves to wear during the summer months. I started composing imaginary stories about gross scars, or bad elbow joints, to tell.

When I got off the plane in Romania, one of the first questions I asked a current volunteer was whether there was a heavy stigma attached to tattoos and body art.

“What? No,” was his casual reply. “Lots of people here have tattooos and piercings.” And he was right.

When I met my directors for the first time (two middle-aged women) I wore long sleeves, despite it being the end of July. When they commented, I showed them my tattoos, and they asked “why would you hide those from us?” It was no big deal, and it was certainly no novelty. One of my best friends at site, Miner, has massive tattoos streaking across his shoulders and down his sides. One out of three guys at my local gym has a visible tattoo.

No volunteer that I know of in Romania, male or female, has ever been discriminated against for having tattoos or piercings. Granted, I receive more attention for them, but no more so than I did in America. I know female volunteers working in small towns that have nose piercings. These are modest in comparison to some of the glittery lip studs a few of my students have.

In retrospect, I figure that my Placement Officer was warning me merely as a matter of policy. In his defense, he had never been to Romania and he had no idea whether the culture really was aversive to body art or not. I imagine that the Peace Corps stance, world-wide, is that tattoos and piercings are a sensitive issue, and should be approached delicately.

I think there is some benefit to this, as no two Peace Corps regions, or countries, or country programs, or even towns are similar. What’s acceptable here in the Jiu Valley may not be in the more traditional Romanian regions of Maramureș, and Oltenia.

But, my advice to any potential/future PCV is this: piercings and tattoos will probably not cause any problems for you at site, despite what your Placement Officer says. Peoples of other countries will typically be flexible about this issue, as you’re an American ambassador, and body art is well-known element of US culture. People will certainly be curious, or fascinated by any tattoos that you have, but your inks will probably never be villified, nor will they ostracize you.

That said, there is time and place for everything. Contact a current volunteer in your assigned country, and see what they have to say. Also, be sensitive to professionalism, and how that relates to your work assignment. For example, I always wear long sleeves when I teach, so that my tattoos are covered. I do this because my directors and I have discussed the issue, and all of us agreed that covering my tattoos while I teach is a good, professional gesture. Almost any American educational institution might ask me to do the same.